As our last major wild food industry, seafood has a much more complex supply chain than other industries. This means that traceability must be robust and all the way through to the label for confidence in its provenance and sustainability.

Compared to other globally traded goods, seafood has a high species diversity, and those species can be incredibly difficult to visually identify. This makes seafood highly susceptible to mislabelling. Without crucial details like what you’re eating, where and how it was caught, Aussies are choosing their seafood blindfolded. Simple, specific, and accurate labelling is essential.

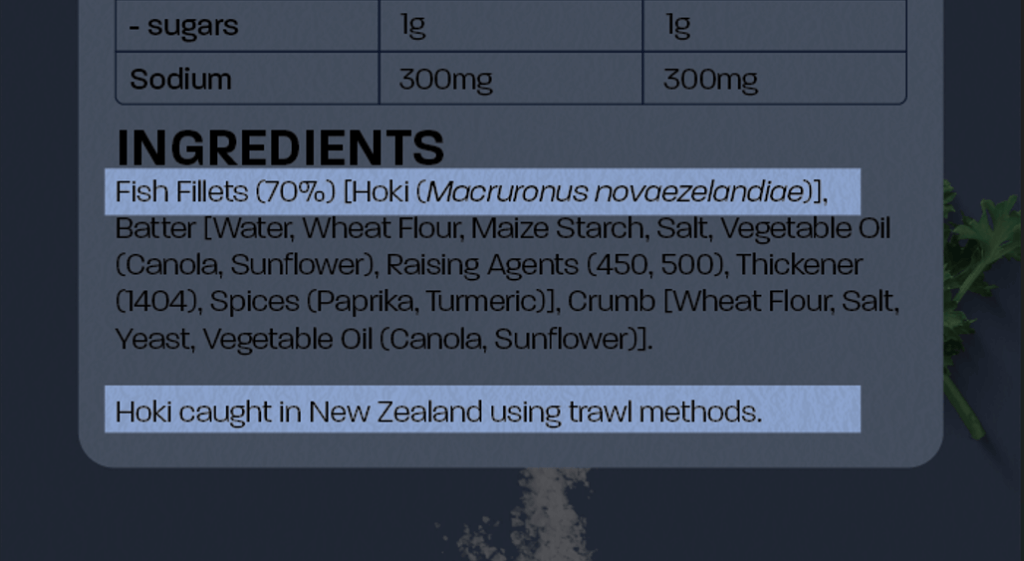

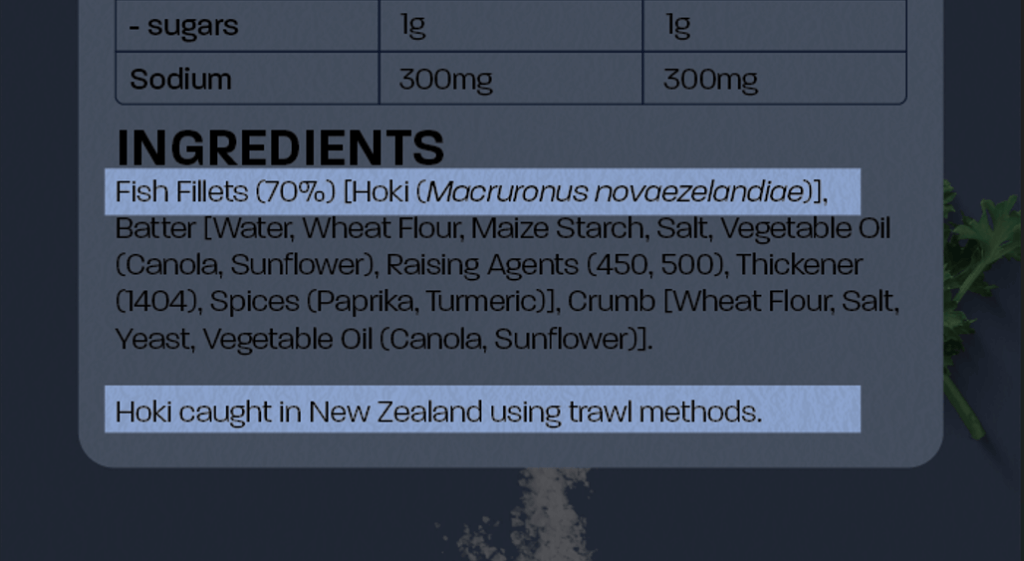

A mockup of what seafood labelling should look like. Simple, specific, and accurate.

Australian labels must be specific and accurate. For Australians to feel confident in their purchasing decisions, all seafood products sold in retailers (e.g. supermarkets, fishmongers, and fish counters) in Australia must include:

- A common name as dictated by the Australian Fish Names Standard, ideally accompanied by an accurate scientific name.

- Point of Capture. If harvested in Australia, it must display the state or territory. If harvested in another country’s or international waters, it must display that country’s name or the FAO Major Fishing Area Code. Farmed products should display either the country they were originally farmed in or, if Australian, the state or territory.

- Whether the product was wild-caught or farmed, and the gear type used in fishing as described in the FAO Standard Gear Types. Farmed products may voluntarily display the farm type.

- Exporting country or country where a majority of processing occurred (if relevant).

Seafood sold through hospitality must also be updated to include:

- A common name as dictated by the Australian Fish Names Standard

- Whether it is Australian (A), Imported (I), or Mixed (M), and if Australian;

- The state or territory of the original harvest.